Passenger train services • Main line services / Ticketing • High speed Rail • Japan

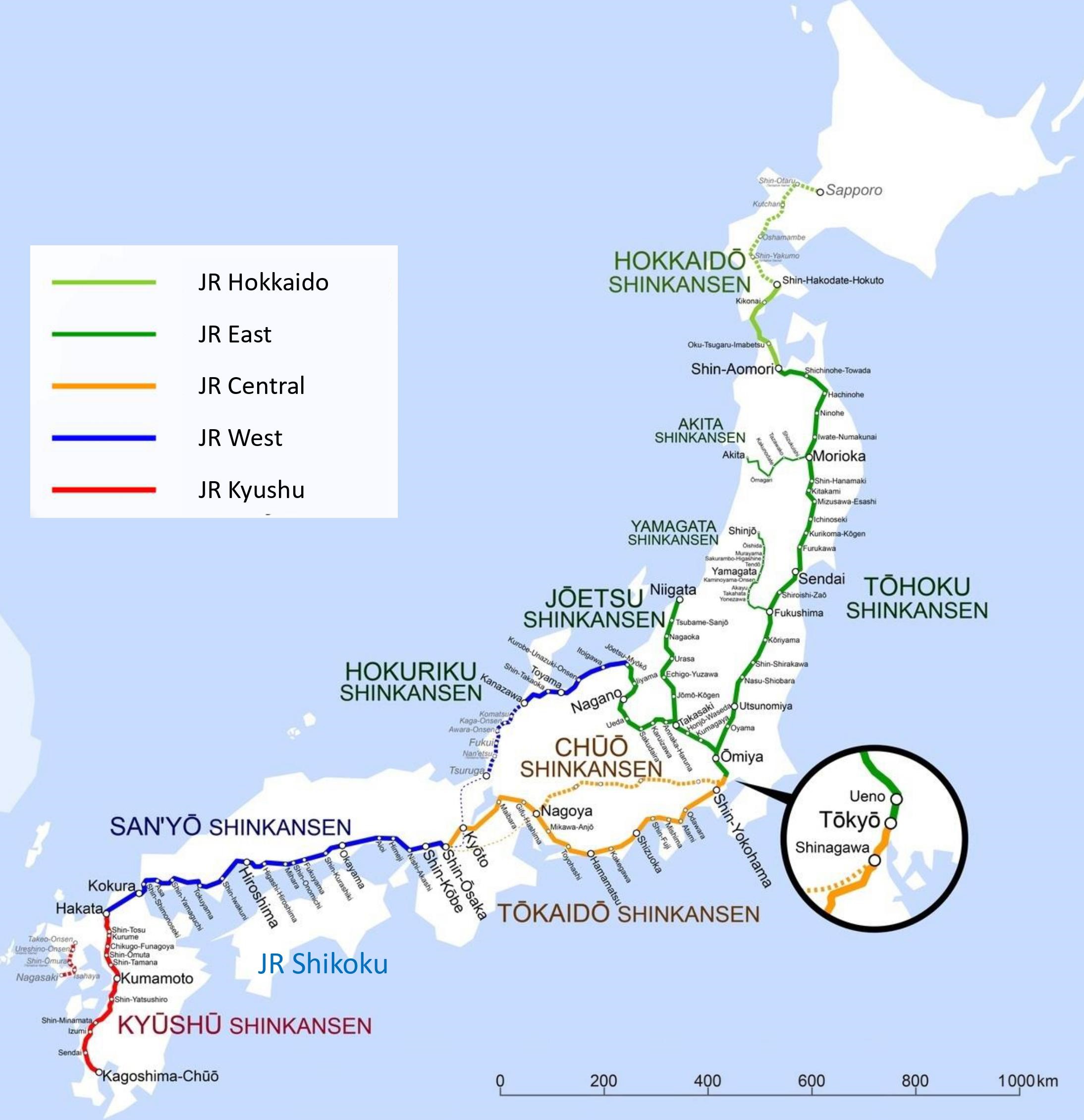

➤ See also: Shinkansen infrastructure and stations – JR Hokkaïdo – JR East – JR Central – JR West – JR Kyushu

➤ See also: High speed train in France – High speed train in Germany – High speed train in Italy – Economics

Note: For educational purpose only. This page is meant purely as a documentation tool and has no legal effect. It is not a substitute for the official page of the operating company, manufacturer or official institutions. It cannot be used for staff training, which is the responsibility of approved institutions and companies.

In brief

Shinkansen (新幹線) is a word for ‘new main line’. It entered Japanese culture in 1939, at a time of Japanese expansionism and the infrastructure projects that accompanied it. In order to meet the nation’s future transport needs, the construction of a high-speed line was established as a necessity.

The Second World War changed all that, of course, and it was not until the 1950s that the Japanese National Railways set up a Committee to investigate the improvement of the Tokaido line, a 1,067mm gauge coastal line.

Infrastructure managers: 5 private companies

Main HS operators: 5 private operators

First services: October 1964

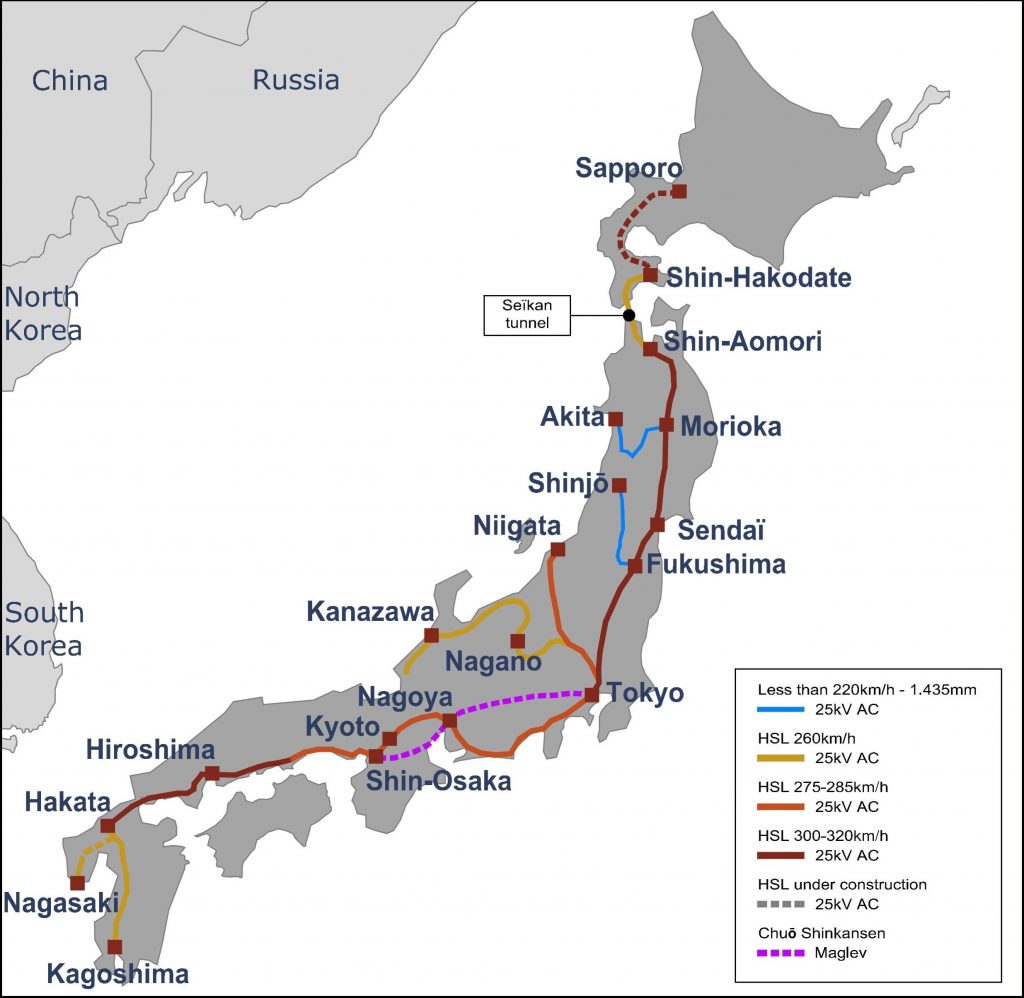

Lenght of network : 2,730km (with reference to lines with ≥ 250 km/h speed, 25kV supply)

In 1958, its conclusions were to undertake the construction of a new high-speed railway, financed by the government and the state-owned company, in order to absorb the increase in traffic forecast for the Tokyo-Osaka megalopolis.

This 515km line was actually built, using the standard UIC 1.435mm gauge, between 1959 and October 1964, just in time for the Olympic Games. It included 12 stations, 3,500 bridges (56km) and 67 tunnels (68km).

The expansion of the network was fraught with difficulties and took place step by step, with Japan exceeding 2,000km of new lines only in 2010. All Shinkansen trains are self-propelled electric trains operating at 25kV, and comprise between 8 and 16 cars, some of which are motorised. Speeds on the various lines range from 240km/h (Tōhoku line from Tokyo to Shinjō) to 320km/h (Tōhoku line from Tokyo to Shin-Aomori).

The definition of a high-speed train varies by region, but generally, it refers to trains that operate at speeds of at least 250 km/h (155 mph) on newly built lines and 200 km/h (124 mph) on upgraded lines. In Europe, for example, the UIC (International Union of Railways) considers a commercial speed of 250 km/h as the principal criterion for high-speed rail. In the United States, the definition can include trains operating at speeds ranging from 180 km/h (110 mph) to 240 km/h (150 mph).

➤ See the UIC definition

Since 1964, 7 series of trainsets with an average age of 20 to 30 years have already been withdrawn from service, with the 400 series, for example, only running between 1992 and 2010. Currently, 9 other series are in circulation on the respective networks of the five companies in charge of operating them (see map below).

At present, Shinkansen services alone – classified as mainline in railway jargon – carry almost 370 million passengers a year (the peak of 386 was reached in 2018).

Network expansion

1964: Tokyo – Shin-Osaka (Tokaido Shinkansen)1975: Shin-Osaka – Hakata (San’yō Shinkansen)

1982: Tokyo – Niigata (Jōetsu Shinkansen)

2010: Tokyo – Shin-Aomori (Tōhoku Shinkansen)

2011: Hakata – Kagoshima-Chūō (Kyushu Shinkansen)

2016: Shin-Aomori – Shin-Hakodate-Hokuto (Hokkaido Shinkansen)

2022: Takeo-Onsen – Nagasaki (Nishi Kyushu Shinkansen)

2024: Takasaki – Tsuruga (Hokuriku Shinkansen)

National rolling stock (past and present)

Unlike other countries, the Japanese high-speed fleet needs to be analysed in terms of the companies that emerged from privatisation in 1987. It is therefore logical to find below only two types of Shinkansen train under the aegis of JNR, Japan National Railway, which bore that name until 31 March 1987.

JNR time – 1964 to 1987

Hitachi, Kawasaki Sharyo, Kinki Sharyo, Kisha Seizo, Nippon Sharyo…

1964 – 2008

Hitachi Kawasaki, Heavy Industries Kinki, Sharyo Nippon,…

1984 – 2012

In April 1987, the Japanese National Railways (JNR) were divided into seven companies: one for freight and six for passenger transport, known as JR. We will briefly present the high-speed rolling stock of each of these companies : JR Hokkaido, JR East, JR Central, JR West and JR Kyushu.

Given the large number of different types of rolling stock, we refer the reader to the respective pages of each company:

➤ JR Hokkaido

➤ JR East

➤ JR Central

➤ JR West

➤ JR Kyushu

Birth of the concept

Japan after the Second World War was a 1,067mm gauge railway that had to fit into a mountainous terrain that was very winding along the coast and inland. Although electrification and modern rolling stock had been introduced, this was hardly conducive to the kind of speed increases seen in Europe.

Before the project was started, JNR had realized that the rapidly increasing passenger demand for Tokaido local line between Tokyo and Osaka would be a serious problem soon. The Annual Transportation Report Book issued by Ministry of Transportation in 1956 said that “even though Tokaido line was just 2.9% (569.5 km) of total railway length in Japan, it carried 26% (36.2 billion passenger km) of total passenger km and 23% (13.1 billion ton km) of total ton km in 1955…So, there was no room to increase frequency”.

From 1958, ‘the business express Kodama’ (photo right above), running at 91 km/h average speed on a conventional line, connected Tokyo and Osaka in 6.5 hours, but service capacity was not enough for increasing travel demands.

As the first action of JNR was to form a research group to study the problem. There were two plans: one was to improve the frequency in the existing local line by expanding its gauge from narrow (1067mm) to standard (1435mm). This is because they expected if they would expand the gauge, they could make their railway operation speed faster. The other was the “bullet train project”: constructing the exclusive line for only high speed passenger railway.

Among those who helped to think a new paradigm were Hideo Shima, the chief engineer, and Shinji Sogō, the first president of Japan National Railways (JNR), who successfully persuaded politicians to support a high-speed rail project. In the early 1960s, no country in the world had a high-speed train.

Very early on, in December 1958, Japan approved the construction of the first segment of what was to be called the Tōkaidō Shinkansen between Tokyo and Osaka. On March 1959, the government approved the budget for the project. The project finance scheme was that the government loan the money to JNR for constructing HSR annually as long term indebtedness, and JNR pay it back from the revenue from the new line.

Work began in April 1959, with vital help from a government loan, railway bonds and another $80 million low-interest loan from the World Bank. The 515-kilometre double-track line links Tokyo and Osaka, the archipelago’s two largest cities. Named ‘Tokaido’, the line uses a gauge of 1,435 mm and a current of 25 kV, two criteria considered world standards by the UIC. However, Japan adopts a slightly wider gauge than Europe, which allows for slightly wider trains, as we shall see later.

The HSR project team had anticipated the possibility of a budget shortfall once the project was underway (as the total cost ended up being significantly higher than their FY1959 estimates). In response, Finance Minister Sato, a strong political advocate for the HSR project, proposed that the Japan National Railways (JNR) secure a loan from the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), also known as the World Bank. Sato argued that even if there were changes in government, the agreement with the IBRD would ensure the project’s completion. In 1961, JNR and the IBRD formalized the financial loan agreement.

1964 – Start of service

The opening was expected to coincide with the Tokyo Summer Olympics, which had already drawn international attention to the country. The Tōkaidō Shinkansen actually entered service on 1 October 1964, with ‘Hikari’ services. Apart from numerous previous trials in various configurations around the world (France in 1955…), this was the first time a line had been dedicated to high speed. At the time, the trains known as ‘Hikari’ only ran at 220 km/h, which was lower than today’s V250 standards, but at the time far higher than any other train in the world, making Japan the first ‘high-speed’ nation.

Japan distinguished itself in 1964 with a different technical approach. In Japan, traction is distributed over several carriages of the train, whereas Alstom and SNCF have adopted the concept of a train framed by two power cars. The Shinkansen 0 series has all its driving axles. It is true that Shinkansen lines have more stops in proportion to their length than high-speed lines elsewhere in the world. The greater width of Japanese trains means that seats can be arranged in a 2+3 configuration in second class (known as ‘Standard’). First class (called ‘Green Class’) adopts the 2+2 configuration. This Japanese configuration was repeated on all subsequent series, making the Shinkansen a high-capacity train. This seating arrangement was a real revelation for European passengers, who were used to having only 2+1 in first class and 2+2 in second class.

The Shinkansen Project

The Shinkansen Project should be considered as an extension of the New Tokaido Project originated by the Japanese National Railways in 1956. When , on 18 May 1970 , the “Law number 71 for Construction of Nation- Wide High-Speed Railways” was adopted by Diet , Article 1 of the law described the purpose of the Shinkansen Program: “In view of the importance of the role pla[1]yed by a high-speed transportation system for the comprehensive and extensive deve[1]lopment of the land, this Law shall be aimed at the construction of a nation-wide high -speed railway network for the purpose of promoting the growth of the national economy and the enlargement of the people’s sphere of life”.

Article 2 defined the term “high-speed railways” herein shall mean the trunk line railway , on the principal section of which operation of trains at high speeds over 200 km/h is possible. Before the act, JNR planned the construction projects of Tokaido and Sanyo Shinkansen, and the government just approved the projects. However after the act, planning, adjustment, and construction order had been under the control of the Minister of Transport as the most responsible person for the realization of the Shinkansen Project and defined the role of the JNR. This means that, after the act, Japanese HSR project was controlled by political sector while the financial and demand risks remained in JNR.

After the Law for the Construction of Nation Wide High-Speed Railways was enacted both the Tokaido Shinkansen and the Sanyo/Shinkansen section between Osaka and Hakata on which construction started before the enactment of the Law / were included in the Shincansen ne twork. The crucial issues of the Shinkansen Project are the geographical configurations of the network as well as the total length of the network .

The Basic Economic and Social Plan, proposed by the Economic Planning Agency and the Economic Council in 1972-71 was approved by the government in February 1973. Shinkansen technological system excellence includes not only hardware and software elements, but also special orgware arrangements, i.e., the establishment of a special Shinkansen task force, JNR and governmental decision making procedure and so on.

1970-1980

The 1970s were however a difficult period for the Japan National Railway (JNR), with local lines running deficits and taking up much of the Tokaido Shinkansen’s profits. This situation led to a lack of development and research to speed up the service over a 15-year period. Despite the difficult financial situation in the 1970s, the loan granted by the World Bank in 1959 was repaid in 1981.

In 1972, Shinkansen was stretched out to Okayama, 150km west of Osaka, and in 1975, to Hakata in North Kyushu, 644km from Osaka. At that time, Shinkansen is composed of 553km of Tokaido Shinkansen and 644km of Sanyo Shinkansen.

It wasn’t until 1982 that the ‘200’ series appeared, which resembled the earlier Series 0 trains, but was lighter and more powerful. Arguably not very innovative at a time when France had launched its own highly publicised high-speed train in 1981, taking the lead in Europe and the world.

Curiously, the 100 series came after the 200 series in 1985 and offered only a slight increase in speed, to 230km/h. In 1987, the series was part of a vast privatisation of JNR, which was divided into 7 separate entities. From then on, each company wanted to compete in terms of technology, and Japan began to build ever more efficient trains, with increasingly pronounced nose modifications.

Meanwhile, the 1,435mm network had doubled in 1975 with the Osaka and Hakata line (513km), giving Japan a 1,000km network just before entering the 1980s. The Ōmiya-Niigata line added 269 km to the network, but it was not until 2010 with the Tokyo-Shin-Aomori line that the 2,000 km mark of high-speed lines was passed.

General technical characteristics before 1990

The Shinkansen’s infrastructure have little spacing between track axis: 4.2 m (in the case of the Tokaido Shinkansen) and 4.3 m (for Sanyo Shinkansen and all thereafter). Cross section in double track tunnels arise about 64 m2. The signalling system is non-reversible and the speed restriction at turnouts into and out of stopping stations arise of 70 km/h.

The Tokaido Shinkansen track features:

• 1435-mm standard gauge;

• CWR and concrete sleepers throughout;

• Movable nodes eliminating gaps at turnouts and crossings;

• Long rails joined by expansion joints to minimize gauge fluctuation due to thermal elongation and shrinkage;

• New-design 53 kg/m rail (50T and later entirely replaced by 60 kg/m rail);

• 25kV AC.

For the first Shinkansen, Japan decided to use ballasted tracks based on the then new theory of ‘optimization of ballasted track considering maintenance requirements’—a wise decision later borne out by the success of the Tokaido Shinkansen. The French and German railway operators had slightly different views about this issue. In France, it was thought that speeds over 200 km/h were possible on ballasted tracks, but in Germany, it was thought that although ballasted track could endure speeds up to 200 km/h, slab track or other types of ballasted tracks would be required for higher speeds.

However, slab track was first used in 1972 on a trial basis in the Sanyo Shinkansen (connecting Osaka to Fukuoka) on certain segments. This marked the first application of slab track for high-speed rail in Japan. The successful implementation of slab track on the Sanyo Shinkansen paved the way for its widespread use on subsequent Shinkansen lines. Starting with the Tohoku Shinkansen and Joetsu Shinkansen in the 1980s, slab track became the standard for new high-speed rail lines in Japan.

Vibration-reducing tracks

A growing social concern is protecting the track-side environment and residents from pollution problems caused by faster train operations or construction of projected shinkansen. Protection from vibration and noise is particularly indispensable. Increasing operation density and other elements are causing growing problems, making it more difficult than ever to maintain normal conditions. Easing the need for maintenance work is also a necessity. The photograph below shows the newly-developed solid-bed track with removable resilient sleepers. In addition to having anti-vibration performance, the sleepers can be replaced easily when elastic fatigue occurs

High-speed turnouts

Earlier shinkansen used 1:18 turnouts because the operation modes did not require high-speed turnouts. However, the new Hokuriku Shinkansen uses a newly-developed 1:38 turnout because the new line branches off the Joetsu Shinkansen at about 3.3 km from Takasaki Station. This new turnout has a lead curve radius of 4200 m, an overall length of approximately 135 m, and a high turnout side speed of 160 km/h.

Difference between Japan and Europe

Technological and service differences between Japan and Europe remain significant, particularly in high-speed rail systems. Japan predominantly uses distributed traction in its Shinkansen, due to design preferences such as coupler quality and the rarity of push-pull systems. Fully-motorized axles, particularly with AC motors, are increasingly favored for their efficiency, safety, and minimized maintenance needs. In the years 80-90, Europe has focused more on concentrated traction (TGV, ICE, ETR and Talgo AVE). Additionally, Japan has developed innovative pantograph systems for current collection, optimizing performance by using dual, electrically-connected pantographs to minimize sparking and ensure continuous power, surpassing the TGV’s single-pantograph system. These distinct approaches highlight regional adaptations in rail technology in the world, where each system best serves the unique needs of its environment.

➤ See our page about the rolling stock

1987 – Privatisation of JNR

Established as a state-owned company in 1949, JNR (Japan National Railways) was profitable and continued to dominate the transport sector until the 1950s. However, competition from other modes of transport intensified and JNR lost its competitive edge. It also had to bear the cost of building the new lines planned by the Committee. JNR recorded a deficit as early as 1964, and this annual deficit continued for many years. By 1987, debts had risen to almost 37.1 trillion yen (about ¥46.33 trillion in 2023 – €297 billion), which was roughly equivalent to the combined national debts of several developing countries.

In addition to financial difficulties, JNR was also the subject of intense public criticism for inefficient management. Privatisation of the organisation was therefore envisaged as a means of resolving the perceived problems of its state-owned status, and the option of splitting JNR into several companies was put on the table to resolve the problems of its monolithic nature on a national scale.

In April 1987, the Japanese National Railways (JNR) were divided into seven companies: one for freight and six for passenger transport, known as JR. This was the first reform of a state-owned national railway in modern history, and preceded similar reforms in other countries. Despite major questions in Europe, this project is considered to be a successful reform of a state-owned company in a Western country.

Of the six new vertically integrated companies, only JR Shikoku does not operate Shinkansen. The other five are shown on the map below:

Since 1987, the Japanese railway model has prospered thanks to a planning system that encourages the construction of commercial and housing developments along the tracks. The Economist explains that JR East owns the land around the tracks and rents it out; almost a third of its income comes from shopping centres, office buildings, flats, etc. This money is reinvested in the network. This money is reinvested in the network. Revenues can be high. Before the pandemic, daily ridership on the shinkansen was around 460,000. There are seven shinkansen departures every hour to the west, from Tokyo to Shin-Osaka.

The network then continued to develop and several series of new trains appeared. The N700-7000/8000 series in service since March 2011 on the Mizuho and Sakura services have a maximum speed of 300 km/h (185 mph). The latest addition is the E8 series ordered by JR East, which is expected to be in service by 2024. Considering the definition of a high-speed line (new or upgraded lines at 250km/h), Japan would rank fifth in the world in terms of kilometres of high-speed network, with 2,730 kilometres.

General technical characteristics since the 90’s

That’s why the harmonization of High-Speed Rail (HSR) technical specifications began in the early 1990s by the International Union of Railways (UIC). The West Japan Railway Company (JR West), Central Japan Railway Company (JR Central), and East Japan Railway Company (JR East) became members of the International Union of Railways (UIC) in the early 1990s:

- JR East joined the UIC earlier, in 1992.

- JR West and JR Central both joined the UIC in 1993.

The UIC played a pivotal role in developing standardized technical specifications for high-speed rail to promote interoperability, safety, and efficiency in the growing high-speed rail sector across different countries and railway systems.

- 1992: UIC started work on standardizing the technical and operational aspects of high-speed rail. This was a response to the rapid development of HSR in Europe (like France’s TGV) and Japan’s Shinkansen, alongside the need to unify specifications across different national systems;

- 1995: The UIC High-Speed Rail Department was established, which contributed significantly to developing harmonized technical specifications. One of the key documents from this period was the creation of the UIC 660 Leaflet, which laid down the basis for interoperability in terms of track gauge, electrical systems, and train dimensions.

It is therefore interesting to compare the main technical criteria developed in the early 90s in many countries in the world:

[TOP]

Infrastructure • High speed Rail • Lexical