Passenger train services • The station and its neighbourhood

Note: For educational purpose only. This page is meant purely as a documentation tool and has no legal effect. It is not a substitute for the official page of the operating company, manufacturer or official institutions. It cannot be used for staff training, which is the responsibility of approved institutions and companies.

In brief

There are many ways of looking at the station, so we’ll confine ourselves to a few themes:

Main stations

• Setting up in the city;

• Architecture of the past;

• Some remarkable stations in Europe;

• Today’s new stations;

The station in its neighbourhood

• The area around the station ;

• Accessibility and public transport ;

• Urban or suburban RER stations ;

Shops and services

• A place to live in the district ;

• Reconfiguration of former stations ;

Rural stations

• The importance of small stations in the past ;

• Yesterday’s architecture ;

• New small stations today ;

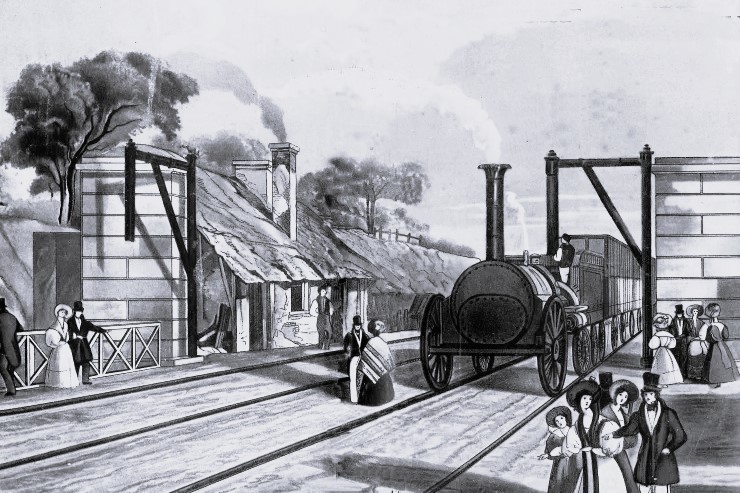

The origins

The station of the first railways, (the ‘embarcadère’ in french), accurately reflects the dual function of the railway: to carry passengers and to transport goods. In a relatively small space, there were halls and facilities for passengers and their luggage, and loading and unloading bays for goods. The size of the expected traffic determines the size of the facilities: there is a long way to go between the modest shelters used on fair days that some small, loss-making companies offer their users and the large stations being built in Europe’s major cities, served by larger companies.

As soon as you moved away from the big cities, you usually found yourself in rural areas with other, much smaller stations. There is very little evidence of the very first rural stations. Logically, they were built as the lines progressed, but they were very basic. The train still served only as an attraction. From the very beginning of the railway, small stops were set up to supply the locomotives with water. It is likely that these stops later became ‘real stations’.

In addition to this technical aspect, small stations were built ‘en dur’, in most cases with very complete facilities: waiting room, toilets, ticket office. The largest of these are of great cultural value and form part of the urban fabric. Almost all of these stations also had a goods yard that was used every day. Coal, in particular, was taken there to provide heating for the local inhabitants. All this is the world of the past. Most of these yards are now used as car parks…

In rural areas, there was either an urban exodus, rendering the short lines and their stations useless, or new housing was built further away from the stations, sometimes by several kilometres. In the meantime, the old cobbled roads had been upgraded with asphalt, speeding up the introduction of the car into households. This socio-economic situation put the railway in danger. Protests from all sides sometimes enabled some stations to be maintained, but for the smallest ones, all that remains today are often just the two platforms, with no facilities. Rural railways and the railways of small towns became more of a disincentive than a means of mobility:

Many of these small stations left a very bad image of the railways and of the state: dirty, old-fashioned places run by the public service, whereas the car industry, which was the product of private industry, was constantly renewing itself and presenting a permanent image of modernity and design. These factors had a considerable impact on the public: fewer and fewer people were taking the route to the station.

The revival

Fortunately, population growth and the limits of a society entirely devoted to the car turned things around in the 1990s. Local rail has been given a new lease of life in countries where the state has finally allowed local authorities to take charge of their stations. In centralist countries, this is still difficult. The current paradox is characterised by the multiple desires of many participants, by the often unsatisfied demands of customers and users, by a building stock that no longer meets current requirements and by the empty coffers of public companies when it comes to concrete investments and improvements to the local situation.

Small stations are now facing new demands for which they have not been adapted. For example, the recognition of autonomy in favour of disabled people has increased significantly, which means that all stations, as well as trains, must be equipped with specific access for people with reduced mobility, which is often difficult to achieve. Other requests concern bicycle ramps to be placed along the staircases to reach the corridors under the tracks. Still others require the return of ticket offices or even ticket counters. All this has a major impact on railway infrastructure budgets, even though these are essential elements of public service.

Renewing small stations does not require major investment, but sometimes simply involves rebuilding both platforms to standard, as shown by the British and Austrian examples above.

Main stations

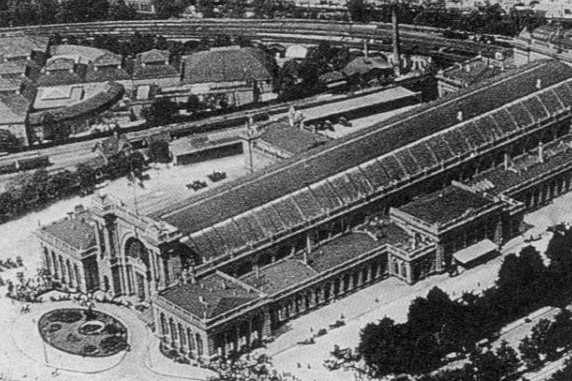

Large railway stations have always been the centrepieces of cities. In the 19th century, many of them were intended to represent the splendour of the railway company that built them. Examples include London-St Pancras (Midland Railway), Paris-Nord (Compagnie des chemins de fer du Nord) and Antwerp (Grand Central Belge). In some cities, such as Paris, London, Madrid or Vienna, this situation led to several large separate stations, often close to city centres which, at the time, were not as extensive as they are today.

In other cases, it was governments that decided to build large stations, such as Budapest-Keleti (1868) or later Milan-Central (under Mussolini). Nowadays, the meteoric expansion of European cities has completely entrenched these dead-end stations in the urban fabric, so that there is often no room for further expansion.

In the second half of the 19th century, the station was a key marker of the emergence of a technical metropolis, a network industry and a society of events and advent,’ explain Nacima Baron et Nathalie Roseau. The photos below show the Gare du Nord in Paris (left) and the Lehter-Bahnhof in Berlin (right), a station that has now been demolished and replaced by the new Hauptbahnhof.

The large urban stations, often destroyed by the war, were modernised and replaced in the 50s and 60s by more functional architecture, at the cost of a certain uniformity. This was the heyday of what has come to be known as Brutalist architecture, the best examples of which include London-Euston and Paris-Montparnasse. This is a very popular architectural style that repeats simple geometric forms, is characterised by the absence of ornamentation and gives pride of place to raw concrete. Liège-Guillemins station (left) and Montparnasse station (right) are emblematic of this highly debatable architectural movement.

But the station is also part of its neighbourhood. Within a jumble of architecture, it often becomes a complex assembly of interlocking spaces and volumes, covered and built or not. Shinjuku station in Tokyo, the largest station in the world with almost 4 million visitors every day, is in itself a collection of structures and buildings, a megastructure, a mosaic of districts, an interior and underground city. This functionalist approach lasted until the 1980s, when France’s TGV (high-speed rail link) signalled a shift towards glass and steel.

The traditional design of stations is no longer seen as simple buildings, but as places where all the city’s transport systems come together. It is this conception of the contemporary station that has made French station architects so successful abroad, in Seoul, China, Turin and Morocco. Another renowned architect, the Spaniard Calatrava, used his talent to design stations such as Liège-Guillemins (pictured below left), Lyon-Aéroport St Exupéry (formerly Satolas) and Lisbon’s Gare do Oriente. Calatrava also designed the Reggio Emilia AV Mediopadana station, an ‘open field’ station on the Milan-Bologna high-speed line (photo right)..

Since the 90s and 2000s, large urban stations have been used for a number of purposes that are not specifically railway-related, but which stem from their role as attractors of more or less captive flows. On the one hand, with the establishment of medium-sized food stores within the station. On the other hand, the intensification of activities and mobility in station areas is generating a dense intermodal offer, which in turn is triggering a sometimes significant attraction for the station itself.

Transformations

And then there are patrimonium. The railways are major landowners and have some of the most impressive property holdings in the country. But what to do with all this heritage? In some cases, maintaining small stations with all their former functions is no longer in line with today’s societal standards, even if there are debates about whether or not to maintain ticket offices and staff. In an increasing number of cases, the buildings still standing have been sold to private individuals or local authorities, who have converted them for other functions. These range from the traditional trendy restaurant to the local library, not forgetting the bike repair shop or the community centre for a small village. These sales are helping to breathe new life into villages and towns that had turned their backs on their station areas. 🟧

[TOP]

Passenger train services • Lexical