Passenger train services • Main line services / Ticketing • High speed Rail • Italy

➤ See also: High speed train in France – High speed train in Germany – High speed train in Japan – Economics

Note: For educational purpose only. This page is meant purely as a documentation tool and has no legal effect. It is not a substitute for the official page of the operating company, manufacturer or official institutions. It cannot be used for staff training, which is the responsibility of approved institutions and companies.

👉 (Version française disponible)

In brief

TAV (Treno Alta Velocità) is Italy’s high-speed train network, designed to connect major cities across the country and beyond. Operated primarily by Trenitalia (through its Frecciarossa service) and Italo, TAV has significantly reduced travel times between key destinations, modernizing Italy’s rail infrastructure and providing an efficient alternative to air travel within the country. Two services dominates the market in Italy:

• Frecciarossa (operated by Trenitalia): This is Italy’s flagship high-speed service, featuring multiple models with speeds up to 300 km/h (186 mph). Frecciarossa connects major cities like Rome, Milan, Turin, Naples, and Venice.

• Italo (operated by Nuovo Trasporto Viaggiatori – NTV): A private competitor to Trenitalia, Italo also runs high-speed trains across Italy, providing another high-quality option for passengers. Italo operates with similar speeds to Frecciarossa and serves many of the same routes.

Infrastructure managers: RFI

Main HS operators: Trenitalia, NTV-Italo, SNCF

First services: June 1977

Lenght of network : 1,067km (with reference to lines with ≥ 250 km/h speed, 25kV supply, ERTMS level 2 and high performance lines >200 km/h)

Major stations include two stations in Milan : Milano-Centrale and Milano-Rogodero, but also Roma-Tiburtina and Roma-Termini, Bologna, Firenze-SMN, Verona, Turin, Venice, Naples, among others. Many smaller cities and towns are also connected to the network through conventional rail lines that high speed train use for part of their journey, like Bolzano or Genoa.

The definition of a high-speed train varies by region, but generally, it refers to trains that operate at speeds of at least 250 km/h (155 mph) on newly built lines and 200 km/h (124 mph) on upgraded lines. In Europe, for example, the UIC (International Union of Railways) considers a commercial speed of 250 km/h as the principal criterion for high-speed rail. In the United States, the definition can include trains operating at speeds ranging from 180 km/h (110 mph) to 240 km/h (150 mph).

➤ See the UIC definition

Network expansion

1977: Direttissima Rome Termini – Città della Pieve1985: Città della Pieve – Arezzo

1986: Florence – Valdarno

1992: Arezzo – Valdarno

2005: Rome Prenestina – Gricignano di Aversa

2006: Turin – Novara

2007: Padova – Mestre (Venice)

2008: Milan – Bologne

2008: Naples – Salerno

2009: Novara – Milan

2009: Bologna – Florence

2009: Gricignano di Aversa – Napoli Centrale

2016: Melzo – Travagliato

National rolling stock from all operators (past and present)

Ansaldo (†), Breda (†), Firema (†), ABB (†), Fiat Ferroviaria (†)

1992 – …

Alstom

2012 – …

Frecciarossa 1000

Bombardier (†), AnsaldoBreda (†)

2015 – …

Alstom

2017 – …

Other rolling stock from foreign operators that runs in France (past and present)

501 – 550 2-current

4501-4540 3-current

GEC-Alsthom

1992 – …

The born of high speed railway in Italy

The idea of a high speed ailway in the 1960s was motivated by several factors related to Italy’s economic, social, and technical needs at the time. Italy, member and founder of the fledgling CEE, was working on creating infrastructure networks that would connect more closely with other European countries, aligning with the growing political and economic integration taking shape across the continent. But at that time Italy’s rail network was facing infrastructure issues and was no longer keeping pace with modern mobility needs. Building a high-speed railway was considered as a step toward greater European integration.

At the time, only Japan had been using the principle of new lines with dedicated trains since 1964, demonstrating the feasibility and conditions required to improve long-distance rail services. The FS studied the possibility of increasing speeds, mainly on the Milan-Naples route, but also on the Turin-Milan-Verona-Venice route.

A new line

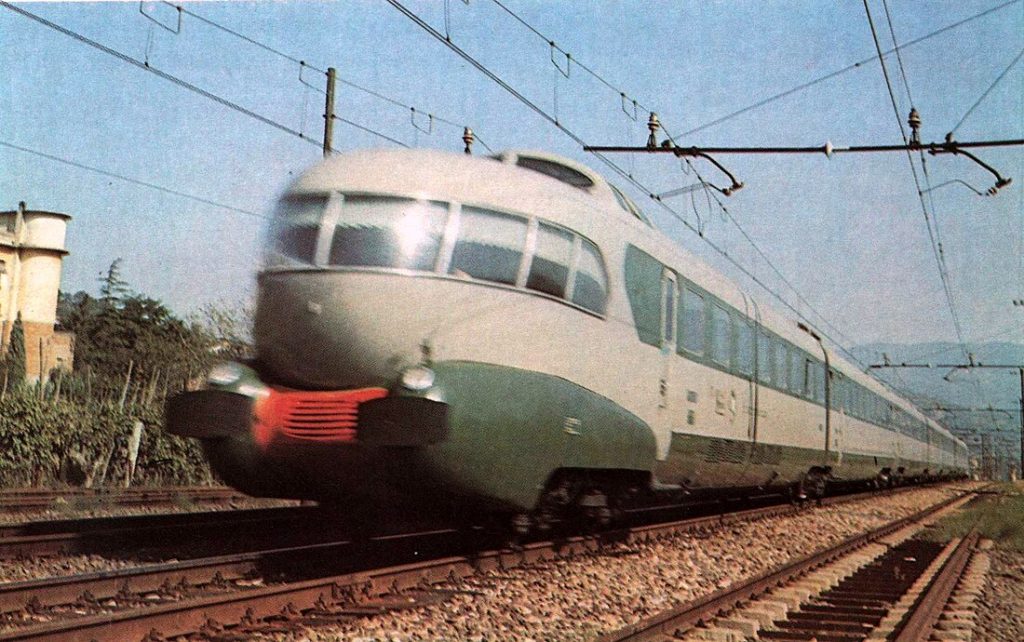

In the 1970s, the Fiat Ferroviaria division brought out a series of trains with tilting bodies called ‘Pendolino’. They were not a great success on Italy’s winding classic lines and, in the eyes of marketing, could not produce a large-scale modal shift. Italian railway engineers then considered something more disruptive.

The decision to build a new railway line between Rome and Florence in the 1970s was driven by several technical, economic, and strategic factors aimed at improving Italy’s railway system.

The original Rome-Orte-Chiussi-Arezzo-Florence line was made up of junctions of a number of sections built between 1859 and 1875 without any overall design. Its purpose was to link various agricultural and commercial centres located between the two towns. It was a very winding line designed in the age of steam trains and had to follow the meanders of the various valleys, which meant a 35% increase in the total journey compared with a route as the crow flies between Rome and Florence. According to UIC criteria, the sinuosity index was 68%. Despite these unfavourable technical factors, in the 1970s this line was used by almost 200 trains a day.

Technical and economic studies highlighted the need to quadruple the track, modernise the construction, reduce the mileage and adopt characteristics that would allow high speeds.

‘Direttissima’ in brief

Italy opted for the construction of new lines that would also accept conventional trains, including freight trains. The Italians were thus closer to the German than the French approach.

The new Firenze-Roma line called ‘direttissima’ line, which literally means ‘direct railway line’, was the first new line project that focuses on high speed. It should not be confused with two earlier ‘direttissima‘ projects, the first that consisted of a direct route between Rome and Naples and the second between Bologna and Florence.

On 25 June 1970, the foundation stone for the ‘direttissima’ Rome-Florence was laid near the river Paglia, where the longest viaduct on the entire line was to be built. Various vicissitudes, both political and economic, have greatly lengthened the construction period and sometimes cast doubt on the choices made by the Italian railways.

24 February 1977 was a historic date: the first section of the ‘direct route ‘direttissima‘ from Rome Termini to Città della Pieve, 138 km long, was officially inaugurated. In a difficult political climate, this was followed by the opening of the Città della Pieve – Arezzo section in 1985 and the Florence-Valdarno section on in 1986.

The last section, Arezzo-Valdarno, was inaugurated on 26 May 1992, a total of 22 years of construction for 262 kilometres. This new high-speed line reduced the journey time from Rome to Florence to one hour and 20 minutes, compared with just under three hours on the best Trans Europ Express lines of the 1980s.

It is therefore appropriate to present Italy as the first European country to have a high-speed line and a high-speed train on its territory, even if at the time the UIC had not yet formally defined the term.

But its opening in the early 90s also coincided with the arrival of a new train never before seen in Italy, the ETR 500, which is why 1992 is remembered as the real starting point for Italian high-speed rail.

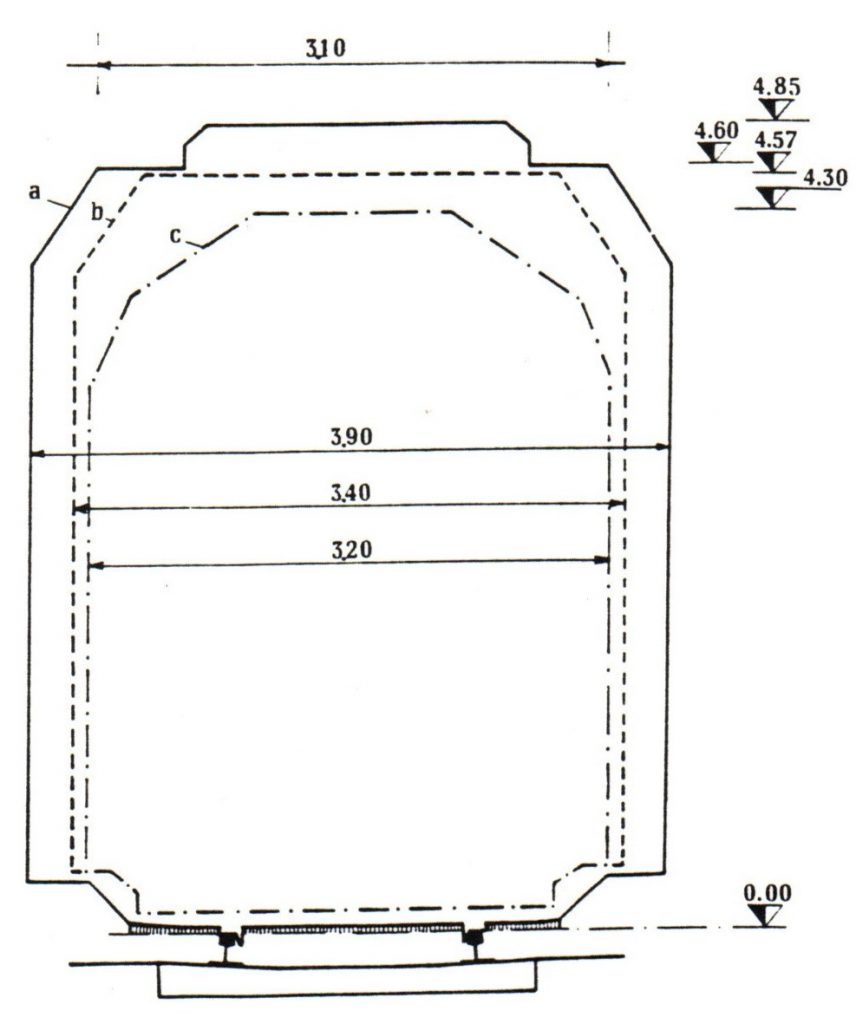

General technical characteristics before 1990

The Italian high-speed rail system aims to be integrated and linked to the existing rail network. Traffic on the new high-speed lines will not be limited to high-speed trains, but will be open to all trains. However, provision has been made for selective traffic, i.e. trains with the same speed characteristics operating during the same time slot. The fact that goods trains will be allowed means that there is a limit to the gradient characteristics. These goods trains should only run at night. This first line, designed using criteria from the 1970s, was limited from the outset to 250 km/h.

The direttissima – which crosses 3 Regions (Tuscany, Umbria, Lazio), 5 Provinces (Florence, Arezzo, Terni, Viterbo and Rome) and 30 municipalities – is 262 km long: it begins at the Station of Settebagni (16 km outside Rome) and terminates at Bivio Rovezzano (4 km outside Florence’s Campo di Marte station).

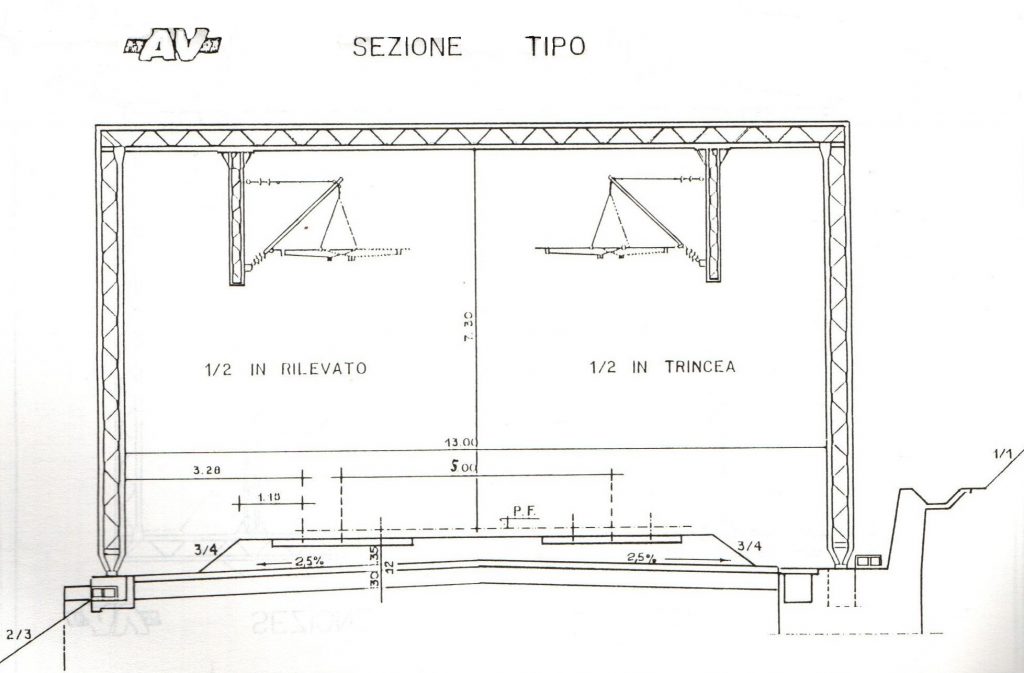

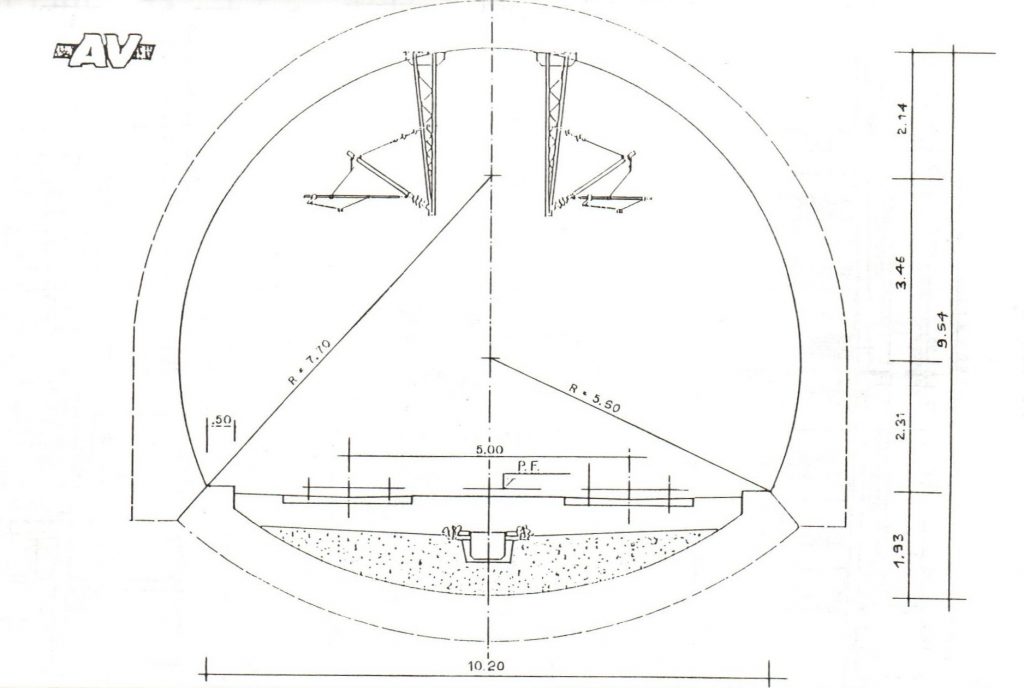

The first new high-speed lines in Italy have been built with a track centre distance of 4 to 4,2 metres and a standard UIC 1435mm gauge. The minimum curve radius R min is 4,000 m, while the maximum cant Dmax is 12.5 cm. In view of the different types of traffic on these new lines, and taking into account the power available and the performance of the locomotives at the time, a gradient limit of around 8‰ has been set for open track and 7.5‰ for tunnels. The platform of the new line is 11 metres wide, compared with 9.86 metres on a conventional line. The line is fully fenced to prevent trespassing and has no level crossings. The connection radius between the slopes on the vertical plane is at least 30,000 metres.

Although built on a new platform, the new ‘direttissima‘ is considered to be a duplication of the classic line as a four-track system. 8 connections with the classic line are planned. The planned route shortened the track between Florence and Rome from 314 to 262 km. Over the entire length, around 30.6 km of the line is on a viaduct, while 74.5 km, or 28.4%, is built in tunnel.

Completing the direttissima took a total of 22 years, with the following opening dates:

- 24 February 1977 – Settebagni – Città della Pieve (Chiusi Sud) – 122 Km (works starting in 1970)

- 29 September 1985 – Città Della Pieve – Arezzo Sud – 52 Km (works starting in 1976)

- 30 May 1986 – Arezzo Sud – Valdarno Nord – 44 Km (works starting in 1984)

- 26 May 1992 – Valdarno Nord – Rovezzano – 20 Km (works starting in 1970).

The Direttissima communicates with the slow line thanks to 10 interconnections that allow numerous interchanges between the two lines. When travelling on the Direttissima from Rome to Florence, the ‘Sud’ interconnections make it possible to leave the Direttissima to return to the old line, while the ‘Nord’ interconnections serve to leave the old line to join the new one.

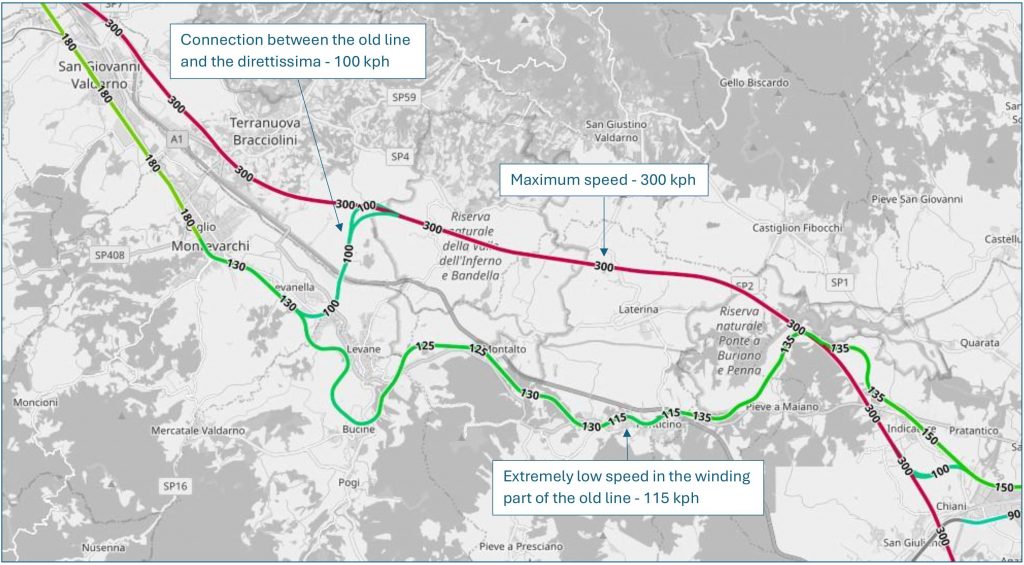

The map below, taken from Open railway map, clearly shows the justification for building the direttissima (in red). On the old line, shown here in green just before Arezzo, speeds plummeted from 185 to 115 km/h and the curves are very winding. Here we see one of the ten connections between the old and new lines, with a speed limit of 100km/h.

The track is equipped with UIC 60 rails, i.e. 60 kg per metre. The sleepers are one-piece concrete sleepers with a lenght of 2.30 m. The ballast will be 35 cm thick, made of basalt rock with a compressive strength of 1,600 kg per cm². The switches between the main tracks can be run at 160 km per hour, while those for the links to the existing line can be run at 100 km per hour.

It was equipped with a 3000V DC catenary, with wires ranging from 450 to 610 mm². It was the only solution available at the time. As a result, there are many electrical substations of 16 km apart.

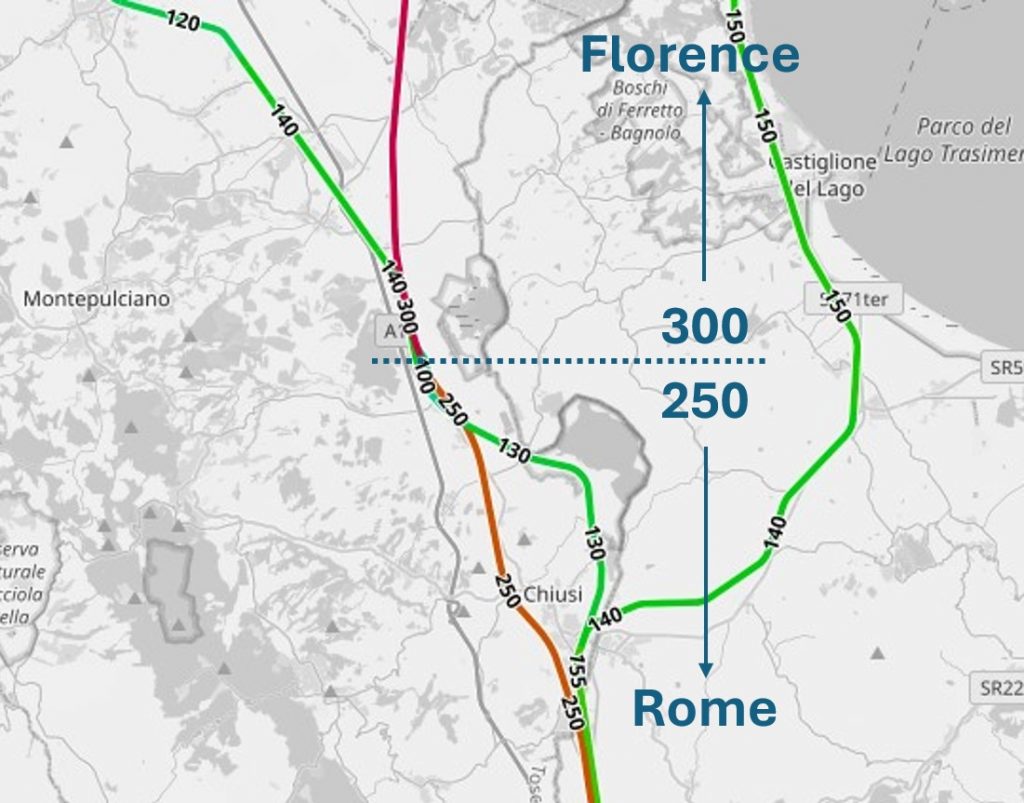

Only the section between Florence and Chiusi-Nord has been designed with a centre-to-centre distance of 4.3m, allowing a maximum speed of 300 km/h. The section between Chiusi-Nord and Rome has a centre-to-centre distance of 4m, which limits its speed to 250 km/h.

Signalling system

At the end of the 1970s, there was still no signalling system in the driver’s cab, so the direttissima was given the classic side signalling. It should be remembered that no specific train was envisaged for this first high-speed line at the end of the 1970s. As a result, the first trains to benefit from the direttissima were conventional trains travelling at speeds of up to 160 km/h, maybe soms reaching 200 km/h. In 80’s, but before ERTMS, the communication with drivers consists of an adaptation of the Italian RS4 Codici train protection system. The term is an abbreviation of Ripetizione Segnali a 4 codici (signal repetition system with 4 codes). The 9-code Coded Current Automatic Block in operation since the 1980s allows maximum speeds of 250 km/h and a minimum distance between trains of 5400m regardless of their speed. We will see later that the direttissima will not be adapted to ERTMS signalling until 2021. The direttissima has therefore been operated with a purely national system since 1977, as well as after its complete opening in 1992.

These technical characteristics will form the basis of the UIC’s high-speed line criteria. Several foreign delegations came to see the Italian technique during the 70s and 80s.

General technical characteristics since the 90’s

Meanwhile, France launched its first TGV high-speed train between Paris and Lyon in September 1981. This train runs on a dedicated line specially designed to reach speeds of 300km/h. Germany and Spain were also building their first high-speed lines. After 15 years of status quo, Japan also began to expand his network.

Three major features mark this new decade of 1990, the last of the twentieth century:

- high speed is no longer just a concept of infrastructure, but also a particular train, designed for high speed;

- trains must be able to leave high-speed lines and reach city-centre stations, always with different signalling and sometimes with a different current;

- Although studied at national level, it appears that the technical criteria are more and more similar.

That’s why the harmonization of High-Speed Rail (HSR) technical specifications began in the early 1990s by the International Union of Railways (UIC). The UIC played a pivotal role in developing standardized technical specifications for high-speed rail to promote interoperability, safety, and efficiency in the growing high-speed rail sector across different countries and railway systems.

- 1992: UIC started work on standardizing the technical and operational aspects of high-speed rail. This was a response to the rapid development of HSR in Europe (like France’s TGV) and Japan’s Shinkansen, alongside the need to unify specifications across different national systems;

- 1995: The UIC High-Speed Rail Department was established, which contributed significantly to developing harmonized technical specifications. One of the key documents from this period was the creation of the UIC 660 Leaflet, which laid down the basis for interoperability in terms of track gauge, electrical systems, and train dimensions.

As a stakeholder in the development of the various standards, Italy has updated the design of its own new high-speed lines, bringing them closer to the standards of neighbouring countries. It is therefore interesting to compare the main technical criteria developed in the early 90s:

Note: this table only shows data from the mid-90s. These data were further refined and extended during the development of the Technical Specifications for Interoperability, the first of which were drawn up in 2006, but only concerned the European Union.

From 12 to 14 November 1990, the very first international seminar on high speed was held in Berlin. Of a total of 38 presentations, 6 were given by Ferrovie dello Stato (FS) managers. Based on the experiences of the five countries, high-speed rail was becoming a major issue in the railway world. The arrival of a more aggressive European Commission on the legislative front paved the way for greater interoperability on the Continent, at a time when the high-speed train was still the object of a national cult.

Numerous seminars have also been held across Europe to exchange experiences. A major step towards greater interoperability was the creation of UNISIG in 1998, as a consortium of railway industry companies to further develop and implement the European Train Control System (ETCS), a key component of the European Rail Traffic Management System (ERTMS). As show above, each country had its own national railway signaling systems, which led to incompatibilities, inefficiencies, and increased costs in cross-border railway operations. At the time, UNISIG brought together major industry players, including companies such as Alstom, Siemens, Bombardier, Ansaldo, and others. With UNISIG, the Italians have been able to integrate their standards alongside those of the French and Germans to develop what would become the future ERTMS/ETCS standards.

As in other countries, Italy moved towards the concept of high speed as a system, and no longer just for doubling up a busy route such as between Rome and Florence. This was to have a lasting impact on the subsequent stages in the construction of the Italian TAV and on the technical caracteristics of the further high speed lines.

The “T” network takes shape

That was the original idea, but we had to wait until the 2000s to see it come to fruition. Since the 1970s, the idea has been to speed up and enhance traffic on the major backbone stretching from Milan to Bologna, Florence, Rome and Naples. To this backbone was added the upper part of the ‘T’, i.e. a line between Turin, Milan, Verona and Venice. This high-speed network considerably reduces journey times between Italy’s main cities, improving internal connectivity and promoting economic development.

However, this original ‘T’ left out Palermo, Genoa, Bari and Catania, respectively 5th, 6th, 9th and 10th cities in terms of population. This is annoying for Genoa, an important city but one that is off-centre and hemmed in by mountains. The case of Bari will be settled more easily, while Catania and Parlermo depend on a fixed link connecting the Peninsula with Sicily.

This “T” was still very incomplete in the mid-90s: only the Rome-Florence section was in service. All the other sections had to be completed. Significant progress was made between 2005 and 2009.

While FS was struggling to put the finishing touches to the direttissima, the state-owned company was already planning a brand new high-speed train in 1983. Like the French TGV, it was to have access to the main stations, which are operated at 3kV. The order was awarded to a highly national consortium set up in 1986, called TREVI (TREno Veloce Italiano). TREVI supplied the 62 FS ETR500 trainsets that run under 1500V, 3kV and 25kV. Their maximal speed was 360 km/h.

These all-Italian trainsets were not used abroad, due to the lack of high-speed lines to France, Austria and Switzerland. It was therefore a product that was emblematic of Italy’s first high-speed period.

➤ See our dedicated pages

The temporary idea of a dedicated operator

As the overall project of the Italian HS-HC was taking shape, the need was felt to create an ad hoc company to raise capital on the financial markets, to be used for the construction of the new high-speed rail transport system, and on 19 July 1991 Treno ad Alta Velocità – TAV S.p.A. was founded for this purpose.

The idea behind the creation of TAV S.p.A. was to adopt a model similar to that used in Japan (as a reminder: the former JNR had been divided into 7 separate vertically integrated companies). The company would have overseen all operations relating to high-speed lines, from the construction of infrastructure (tracks, stations, electrification) to the management of trains and associated services. In theory, this would have enabled better integration between line planning, train operation and maintenance, ensuring high efficiency and performance.

A number of Italian and foreign credit institutions (including IMI, Citibank, Banca Nazionale del Lavoro, Istituto Italiano di Credito Fondiario, Banco di Napoli, Cariplo, Sanpaolo IMI, ISVEIMER, Crediop, Credito Italiano, Indosuez, Credit Lyonnaise) held 55.5% of the company’s share capital, and Ferrovie dello Stato held the remaining 45.5%. Between August and September 1991, the company received from the holding company the activities relating to the design, construction and economic exploitation of the high-speed system for the next 50 years. The aim was to realise the project financing.

In 1996, Ferrovie dello Stato revised the agreement, obtaining the right to operate high-speed services itself: in return, it would pay Tav a fixed annual toll, independent of network use. Shortly afterwards, however, Ferrovie dello Stato again requested a change to the contract with TAV, alarmed by the high price of Av tracks, the incessant delays on construction sites and the fact that revenues from Av transport would go to TAV spa. For their part, the banks were beginning to worry about the lack of a legislative framework regulating rates and access to infrastructure, as well as the political and bureaucratic paralysis of the authorities.

In 1998, Ferrovie dello Stato took over 100% of TAV from the 42 private institutions. The withdrawal of the private sector was offset by loans granted by Infrastrutture S.p.A. from the early 2000s.

Between 1992 and 2001, as part of a wider reform of the European rail sector, the former FS administration was evolving into a holding company. The following key dates stand out:

From then on, the TAV network was built under the aegis of RFI, which still exists today. The idea of creating an independent TAV company as explained above was definitively canceled with his incorporation into RFI in 2010.

The high speed network since 2000

In addition to the fundamental reform of the old FS administration, the early 2000s were marked by a series of fundamental changes in the rail environment:

- increasing internationalisation of the industry through consolidation and various mergers between manufacturers ;

- the future development of a European directive on technical specifications for interoperability (TSIs) by branch. The first TSI concerned high-speed rail;

- the future development of a European directive on the new ERTMS/ETCS traffic control and signalling system, originally intended as a priority for high-speed.

So there were all the ingredients to modify the technical parameters of high speed in relation to the experience gained from the Rome-Florence Directive and to align with European standards. It should be noted that these standards were not invented by the EU, but were technical criteria patiently developed by the UIC in the 90s, and which became law through EU directives.

The first high-speed Technical Specification for Interoperability (TSI) at EU level appeared in 2002. It was adopted as part of Directive 96/48/EC, which aimed to develop an interoperable rail network and encourage sustainable transport on a European scale. This TSI already covered in detail track and gauges, bridges and tunnels, standards for station design, 25 kV, 50 Hz alternating current electrification systems used on many high-speed lines, standards for pantographs and their interaction with catenaries, control-command and signalling via the ETCS (European Train Control System), and so on.

During the construction of direttissima Rome-Florence, the problems caused by the insertion into the environment of this new infrastructure were also addressed, adopting mitigation measures for the first time on high speed lines in Italy. With the construction of the new high speed lines between Turin, Milan and Naples the need arose to reexamine the characteristics of the direct Rome-Florence line.

All this has had a lasting impact on the design of Italy’s future high-speed lines. What’s more, for construction sites, calls for tender above a certain figure had to be made at European level. In 2005, the minimum threshold above which a call for tenders for works contracts (including civil engineering) had to be published at European level was €5,923,000 excluding tax. This threshold was applicable under the European directives in force at the time, principally Directive 93/37/EEC, which governed public works contracts until the introduction of Directive 2004/18/EC (adopted in 2004 and phased in from 2006). This amount changed several times over the next twenty years, but was always around 5,000,000 euros.

Upgrade of Direttissima

The upgrading of the direttissima to conform with the standards of the new high speed lines under construction required works on existing civil engineering structures (tunnels, viaducts etc), electrical traction facilities, signalling and telecommunications. It is proposed to raise the maximum speed from 250 km/h to 270 or 280 km/h. It has additionally been proposed to re-electrify the line at 25 kV AC in the past but this has been abandoned.

The signaling, however, has completely abandoned the RS9 Codici in favor of ETCS Level 2, installed between December 2020 and 2024.

The TSIs are legal documents, being issued by the European Commission and their requirements are applicable and mandatory for all the subsystems and components covered by the scope of the relevant TSI. The Council of the European Union has adopted directive 96/48/EC of 23 July 1996 on the interoperability of the trans-European high-speed rail system. The first set of TSIs for high speed rail system was developed in 2002, around the time of adoption of the first interoperability directives. These TSIs were developed by an organisation created especially for this purpose; the European Association for Railway Interoperability, commonly known under French name Association Européenne pour l’Interopérabilité Ferroviaire (AEIF). The first TSIs were related to infrastructure (HS INF), energy (HS ENE), rolling stock (HS RST), control-command and signalling (HS CCS), and traffic operation and management (HS OPE) subsystems of the trans-European high speed railway system.

2005: Rome – Naples

The direttissima central section inaugurated in 1992 was just one link in a magisterial ‘T’ stretching from Milan to Naples. All that remained to be done was to build the other missing links, both to the north and to the south. Ferrovie dello Stato had been studying the future of the high-speed network for several years. Joining from Rome to Naples quickly became a priority.

After an extensive surveying effort, a route for the proposed railway was finalized, spanning a total distance of 204 km, with approximately 13% (28.3 km) of the route passing through a network of bored tunnels. Early in the planning phase, it was determined that the construction program should be divided into multiple segments, each corresponding to different sections of the railway. These segments were released for competitive tender, during which bidders submitted detailed design and engineering proposals for their respective civil works. As a result of this process, contracts were awarded to five contractors – Pegaso, Icla, Italstrade, Vianini, and Condotte. These firms were also collectively appointed as the general contractor for the entire project under the IRICAV UNO consortium.

Construction of the railway began in May 1995, focusing primarily on underground works through volcanic rock. Techniques like shotcrete and fiberglass elements were used to stabilize areas prone to deformation. Access tunnels large enough for vehicles accompanied some of the longer tunnels. By 1999, 99% of the railway’s tunnels were completed, averaging a daily advance of 20 meters. The geological conditions supported efficient construction, minimizing cost overruns. All civil engineering works were finished by March 2001.

The railway’s longest tunnel spans 6,725 meters, with a maximum gradient of 21‰. In 2004-2005, tests confirmed the line’s suitability for speeds up to 300 km/h, with an ETR 500 train reaching 347 km/h. This was facilitated by 25 kV AC electrification and the European Train Control System. The first section, 193 km long, opened on 19 December 2005, connecting Rome to Naples with several interconnections to the historic Rome-Naples line.

This second high-speed line brought Italy closer to European standards, especially since the High-Speed Technical Specifications for Interoperability (TSI) were already in effect by that time. The line was directly electrified at 25 kV, which consequently required the use of dual-voltage ETR 500 trains to access the stations in Rome and Naples, both electrified at 3 kV DC. The speed is 300km/h and the signalling installed is an early version of ETCS level 2. We’re well within the European criteria.

The 2009 winter timetable marked the start of commercial operation of the terminal section between Gricignano di Aversa and Naples Central station. Since 13 December 2009, the line connect Rome and Naples in 1 hour 10 minutes.

2006-2009: Turin – Novara – Milan

The route, between the former Bivio Stura, in the Settimo Torinese territory, and the Milano Certosa station, is 126 kilometres long, of which 99 kilometres in the Piedmont territory and 27 kilometres in the Lombardy territory. The rest of the route, between Torino Porta Nuova and Torino Stura and between Milano Certosa and Milano Centrale station, is shared with the double track of the existing line. This is the first upper branch forming the T of the network.

The line is supplied at 2x25kV and complies with European standards, with the application of ERTMS. The section between Turin and Novara was first opened to rail traffic on 7 February 2006. The second part, between Novara et Milan, was officially opened in two step to a full opening on 5 December 2009. The implementation of the ERTMs did not allow SNCF’s TGV-Réseau trains to benefit from the new line on the route Paris-Modane-Milan. French trains could only travel to Italy via the conventionnal line.

The line crosses the territory of forty-one municipalities. The flat conformation of the territory has allowed the line to be developed for 80% (about 100 kilometres) at ground level, with some limited stretches in trenches, 15% (about twenty kilometres) on viaducts and only 5% (just over five kilometres) in artificial tunnels. Among the most important works are the Santhià viaduct, 3.8 kilometres long, and the Rondissone artificial tunnel, 1688 metres long.

Milan-Venice

The Eastern branch of the TAV high-speed network is more complicated to build. It will link Milan with Verona and Venice, two of the country’s major cities. This Eastern branch is made up of multiple sections, some of which have undergone major route revisions. At present, only a small section from Padua-Montà to Mestre (at the entrance to Venice) is in service.

2007: Padua-Venice

The section between Padua and Venice, 29 kilometres long, was the first of the projetc, inaugurated on 1 March 2007 and cost 467 million euros (20.3 million euros per kilometre). Unlike other new lines, this is a doubling of the conventional line, with a speed limit of 220km/h and 3kV DC electrification. According the UIC’s criteria, this section can considered an upgraded lines rather than a new line.

Unlike the entire high-speed system in Italy, it is the only infrastructure that the entire project has not been built through a general contractor contract. Originally it was supposed to be designed and built as one piece by IRICAV Due, according to the 1991 agreement with TAV, but in 1993 this contract was terminated. In 2002, the construction of the main civil works on Padua-Mestre (Venice) (29% of the total cost of the project as well as 50% of the budget for works alone) was entrusted to a temporary consortium of Baldassini-Tognozzi-Pontello and Matarrese.

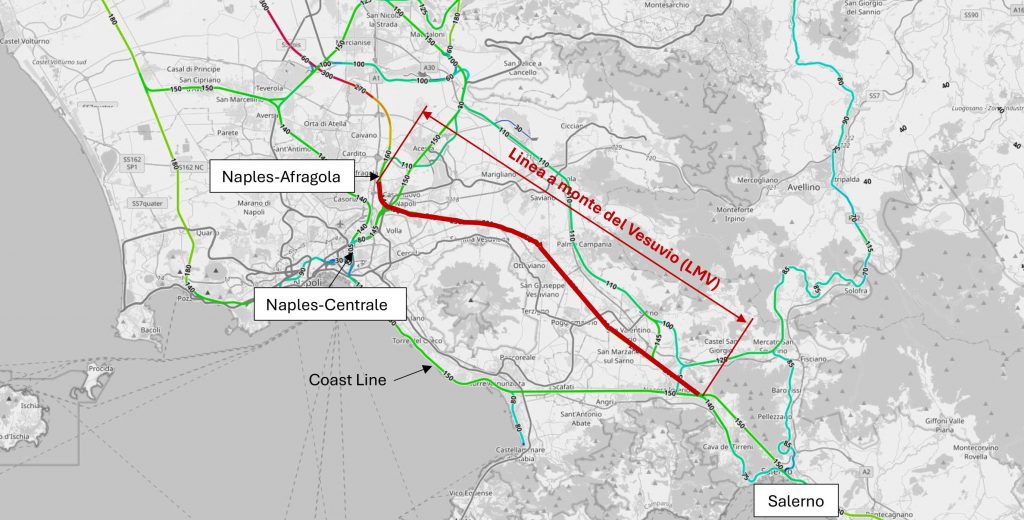

2008: By pass Linea a monte del Vesuvio (LMV)

The Linea a monte del Vesuvio (LMV) (also known as the Naples-Salerno via a monte del Vesuvio railway and abbreviated to LMV) is a bypass of Naples along an inland stretch, skirting around Mount Vesuvius to the east (in red). The aim is to reach Salerno more quickly and avoid the historic and very busy coastal line (in green). Bypassing Naples from the north was the reason for building the new Afragola station, which was inaugurated much later, in 2017.

This railway line was built on the model of the direttissima Florence-Rome. Once again, it sets itself apart from European standards with its 3 kV DC electrification and traditional signalling with 9-code signal repetition and SCMT. The speed limit is 250km/h. It was inaugurated in June 2008.

A similar project with an external station at Salerno is envisaged to bypass the city and continue with a new 300km/h line to Reggio di Calabria, at the gateway to Sicily. But today, TAV trains still get off at the centre of Salerno.

2008: Milan-Bologne

It was one of the big missing pieces. The rather straight Milan-Bologna section brings the capital of Lombardy closer to the country’s capital. The speed is 300km/h with ETCS level 2 signalling. A new feature of the line is the construction of a new station close to Regio-Emilia. With the exception of the north of Naples (more on this later), Italy has not until now been tempted by new stations located outside towns, as is the practice in France and Germany.

The quadrupling of the Milan-Bologna line, with the construction of a dedicated high-speed line, was announced in the press in January 1988. The slowdown of the entire restructuring project of the former State Railways due to the various judicial events of the period meant that it was only in December 1993, during the Services Conference for the Milan-Bologna line, that the discussion began again in concrete terms, leading to the approval of the executive project.

The first section is a four-lane line from Milan Rogoredo to Bivio Sordio, created to free the Rogoredo-San Zenone al Lambro. It was opened on 1 June 1997 by what was still Ferrovie dello Stato (FS). It was an infrastructure that served to improve circulation near the Milan junction and was therefore conceived and built with criteria identical to those found on all other Italian lines.

In 2002, construction sites were opened for the quadrupling of the remaining line. On 11 September 2005, the Castelfranco-Lavino section was opened, while on 10 October 2007 the section between Lavino and the Santa Viola station was opened.

In November 2007, both the laying of the tracks and the preparation of the technological systems and power line for the rest of the railway were completed. On 16 December 2007, the cycle of tests in preparation for its opening began. During these tests, on 1 March 2008, the ETR 500 Y1 RFI convoy of RFI S.p.A. reached a speed of 355 km/h, beating the previous record of 352 km/h, which had been set on 25 May 2006.

The inauguration of the entire line took place on 13 December 2008 with a maiden voyage made by an ETR 500 Frecciarossa, classified as ES AV 29405. The opening to commercial traffic took place the following day, following the introduction of the new Trenitalia timetables. The inauguration cut the Milan-Bologna journey time to 55 minutes.The inauguration cut the Milan-Bologna journey time to 55 minutes and marked a turning point in the Milan-Rome traffic offer, especially as the Bologna-Florence section was about to open.

2009: Bologna – Florence

Of the 79 kilometers that unite Bologna and Florence as many as 73.8 run through tunnels, the most extensive underground system in the world. It involves the territory of 12 municipalities, 6 in the province of Bologna and 6 in the province of Florence. It starts on the outskirts of Bologna, where it immediately faces a 61-meter bridge over the Savena stream. Then you arrive at the Pianoro tunnel, almost 11 km long. At the tunnel’s exit, a 121-meter-long bridge crosses the Laurinziano and Crocione streams. It is then the turn of the Sadurano tunnel (3.8 km), which ends on the rio dei Cani gorge, crossed by a box viaduct. A trench section follows until the Monte Bibele tunnel (9.2 km) at the end of which the line faces the valley of the Idice Torrent with a bridge. Immediately after is the turn of the Raticosa tunnel (10.4 km) where the line touches 413 meters above sea level, the highest elevation of the line. There is then the viaduct crossing of the Diaterna stream, followed by the 3.5 km Scheggianico tunnel to the Santerno Valley, where another bridge crosses the river of the same name.

One of rare uncovered points is the San Pellegrino station (and adjoining rock chamber) in the Santerno valley, about halfway along the route. It is used for the maintenance of the rail network and will allow the stopping of freight that will have to give way to fast trains. The High Speed route then enters the Firenzuola tunnel , more than 15 km long, and then exits into the Mugello Plain. Two more tunnels are passed: the Borgo Rinzelli tunnel (717 m) and the Morticine tunnel (654 m). The journey then continues in the open until the Vaglia tunnel, over 18 km long, the longest tunnel on the line, which passes through the municipalities of Vaglia and Sesto Fiorentino before arriving at Castello station, the entry point into the Florence area.

The line was inaugurated in 14 December 2009, and make it possible to join Bologne with the capital of Tuscany in 30 minutes.

2009: Gricignano di Aversa – Naples Centrale

Strictly speaking, this is not a TAV line, but a quadrupling of the tracks to increase speed at the entrance to Naples. The fourth interconnection, known as the Gricignano di Aversa interconnection, was essential before the completion of the last section of the high-speed line (AV), which connects the First Gricignano Junction to the Casoria Nord Junction. During this time, it was used to route high-speed trains onto the historical railway, providing a temporary solution to maintain high-speed service continuity.

Subsequently, with the completion of the final section of the AV line, the primary function of this interconnection changed. It now plays a secondary but crucial role as a technical rescue interconnection. This means that, in case of emergencies or the need for temporary diversions, AV trains can use this interconnection to switch from the high-speed line to the historical line, ensuring greater flexibility and resilience in managing railway traffic

The 2009 winter timetable marked the start of commercial operation and from December 13, the full TAV line could connect the cities of Rome and Naples (Centrale) in 1 hour and 10 minutes.

Since then, a significant part of the famous high-speed “T” network has been in service, from Turin to Salerno. Since December 2009, the opening of several high-speed lines in Italy has significantly transformed train schedules and traffic across the national railway network. This shift introduced a more efficient and competitive mode of transportation, cutting travel times between major cities and reshaping passenger habits. For example, the connection between Milan and Rome, previously a journey of nearly six hours on traditional lines, now takes just under three hours on the high-speed line. This reduction in travel time has made high-speed rail a highly attractive alternative to both car and air travel, especially for business commuters who benefit from the reliability and comfort of high-speed trains.

A consequence of the high-speed network expansion has been a rethinking of ticketing and pricing strategies. High-speed services now offer a range of fare options, catering to different customer needs and increasing accessibility. This new system, coupled with the reduced travel times, has led to significant growth in passenger numbers, challenging the dominance of airlines on domestic routes.

In April 2012, the Italian railway landscape welcomed a new operator, NTV-Italo, the first significant competitor in the high-speed sector, which had been dominated by Trenitalia until that point. Founded by prominent entrepreneurs like Luca Cordero di Montezemolo and Diego Della Valle, NTV launched Italo with the aim of providing an innovative and quality alternative to travelers. This new railway entity introduced modern trains equipped with advanced technologies and top-notch services, making the journey more comfortable and enjoyable.

Italo focused on distinctive features such as flexible travel classes, ranging from economy to Club Executive, and personalized services like free Wi-Fi and access to multimedia content. The debut of NTV-Italo also marked a price revolution, thanks to a competitive pricing policy that made high-speed travel more accessible. For its services, NTV made an ambitious choice from the outset, opting for a massive investment of more than €1 billion, including €628 million just for the purchase of 25 new high-speed trains that only existed on paper.

➤ See our dedicated page

Around 2013 and 2014, the Italian railways underwent significant changes marked by structural reforms and the introduction of a new regulator. The reforms were implemented under the government of Enrico Letta, who served as Prime Minister from April 2013 to February 2014. These modifications had a profound impact on the Italian railway system, making it more competitive and market-oriented.

One of the most relevant changes was the establishment of the Transport Regulation Authority (ART), created in 2014 to ensure greater transparency and competition in the sector. This authority is responsible for overseeing tariffs, service quality, and access to infrastructure, promoting a balance between the needs of various railway operators. With the presence of ART, a new culture of accountability and performance was introduced, encouraging companies to enhance their services to attract more passengers.

At the same time, the Ferrovie dello Stato Italiane (FS) group underwent a significant transformation. The restructuring led to a clearer separation between infrastructure management and operational functions. This process favored greater efficiency and allowed the group to focus on innovation and modernization of services. The entry of new operators into the market, such as Italo, intensified competition, compelling FS to improve service quality and adapt to customer needs.

Rete Ferroviaria Italiana (RFI) plays a crucial role in managing the high-speed railway (TAV) network in Italy. Its main responsibility involves the design, construction, and maintenance of TAV infrastructure, ensuring safety and quality standards. RFI is also responsible for capacity planning on the network, ensuring that services are efficient and regular.

➤ See our dedicated page

The Milan-Verona-Venice TAV

It is with this entirely new institutional and commercial landscape that the continuation of the network construction proceeds. Rete Ferroviaria Italiana (RFI) secured funding for the high-speed railway (TAV) between Milan and Venice through a combination of strategies and agreements. Firstly, the project was included in the National Transport Plan, which provided a regulatory and financial framework for the development of railway infrastructure. This inclusion allowed RFI to access national and European public funds aimed at improving the railway network.

Additionally, RFI collaborated with the Ministry of Infrastructure and Transport, which supported the funding request at the European level. The European Union recognized the importance of the Milan-Venice TAV as part of the Trans-European Transport Network, facilitating the allocation of resources through the Connecting Europe Facility (CEF) program.

The Milan-Venice route concentrates large towns every 70 km or so: Brescia, Verona and Padua were to form part of the TAV. So it was decided not to repeat what was done in Naples, by bypassing the central station. The Milan-Venice TAV line therefore comprises the following short sections:

- Melzo-Travagliato (west of Brescia) – ETCS, 300km/h, 25kV ;

- Calcinato (east of Brescia) – Verona West – (under construction – ETCS, 250km/h, 25kV) ;

2016: Melzo-Travagliato

The high-speed rail line (TAV) between Melzo and Travagliato (west of Brescia) is part of the rail corridor connecting Turin to Venice, improving travel times and transportation capacity between major cities in northern Italy.

The previous project for the continuation between Brescia and Verona envisaged the passage of the high-speed railway south of the city of Brescia and alongside the A21 motorway junction, along the so-called ‘Brescia shunt’. In 2015, Ferrovie dello Stato proposed to revise the route, eliminating the shunt and maintaining only the interconnection from the Brescia Ovest to the Brescia existing station: this proposal was approved by the CIPE on 10 July 2017. The Interministerial Committee also approved the design of the quadrupling alongside the historic line from Brescia station to the Brescia East interconnection.

This short line was inaugurated on December 10, 2016. With the opening of this section, high-speed trains can cover the distance between Milan and Brescia in about 36 minutes, enhancing connectivity between Lombardy and the rest of the country. 🟧

👉 (Version française disponible)

Infrastructure • High speed Rail • Lexical

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————-